When Henry Ford died in April 1947, his industrial empire was in a precarious position. Any muscle the Ford Motor Company has previously flexed had sagged and grown sallow after years of stubborn complacency from its founder.

One could argue that the company’s decline had begun in the mid-1920s when Henry spurned attempts to upgrade or replace the incredibly successful Model T, introduced in 1908. The Model A was introduced for 1928 and was a hit, but competitive forces, especially from General Motors’ surging Chevrolet division, demanded more change, which came with the first Ford V8s in 1932.

Although the V8 was an engineering triumph and Ford remained an industrial colossus in the 1930s, the company had lost its edge. Early in the decade, Chrysler Corporation became the No. 2 Detroit automaker, while Ford slipped to third. It would remain there for two decades.

Much of the company’s hope was riding on the shoulders of Henry’s only son, Edsel, but Edsel’s many attempts to modernize the company were often sabotaged by Henry. Yet when Edsel died in May 1943 of stomach cancer, even the United States government was worried. The Ford Motor Company was key to the Allied effort and substantial contracts had been awarded for the building of military machines. Chief among them was Willow Run, a massive factory that would produce bombers.

So worried was Washington that the government permitted Edsel’s oldest son, Henry Ford II, to leave the navy in the hope the oldest Ford grandson would help the company survive some of its internal turmoil and Old Henry’s senility.

How bad was it at the Ford Motor Company? According to many accounts, Ford’s factories were in great need of upgrading.

And incredibly, its finances were so unorganized that observers reported that accountants regularly weighed invoices to determine approximate values. Old Henry had so despised accountants and controllers that the company’s finance department had been stripped of most of its authority and most of its employees.

Equally troubling was the Ford workforce. The Ford Motor Company had been the last major Detroit-based carmaker to accept the demands of the United Auto Workers, and then only after bloodshed and death. But even with a union in place, the company sponsored a murky, almost Mafia-like security organization to maintain order on the factory floor.

When Henry Ford II became an executive of the company in August 1943, his first task was to rid the company of the leader of its security force, Harry Bennett, whose power had once rivalled that of Old Henry’s. But it wasn’t until September 1945 that the Ford grandson assumed complete control of the company. He turned 28 that month.

Young Henry realized he needed help, and his first major decision was to hire a group of young men who had established a reputation during the war for maintaining statistical records for the air force. Known as the Whiz Kids, they brought the necessary discipline to Ford’s finances. Among the Whiz Kids was Robert McNamara, who would leave Ford 15 years later to become Secretary of Defense for the Kennedy Administration.

Henry Ford II’s second decision was to hire Ernest Breech away from General Motors. Breech was tasked with reorganizing the Ford Motor Company’s production and improving its product. Almost immediately, his focus was on a completely new Ford, to be introduced for the 1949 model year.

At the time, Ford was producing cars that were warmed-over pre-war models. It wasn’t alone; it was the same at GM and Chrysler.

But as the No. 3 automaker, Ford’s position was more precarious and so a lot more was riding on a completely new car.

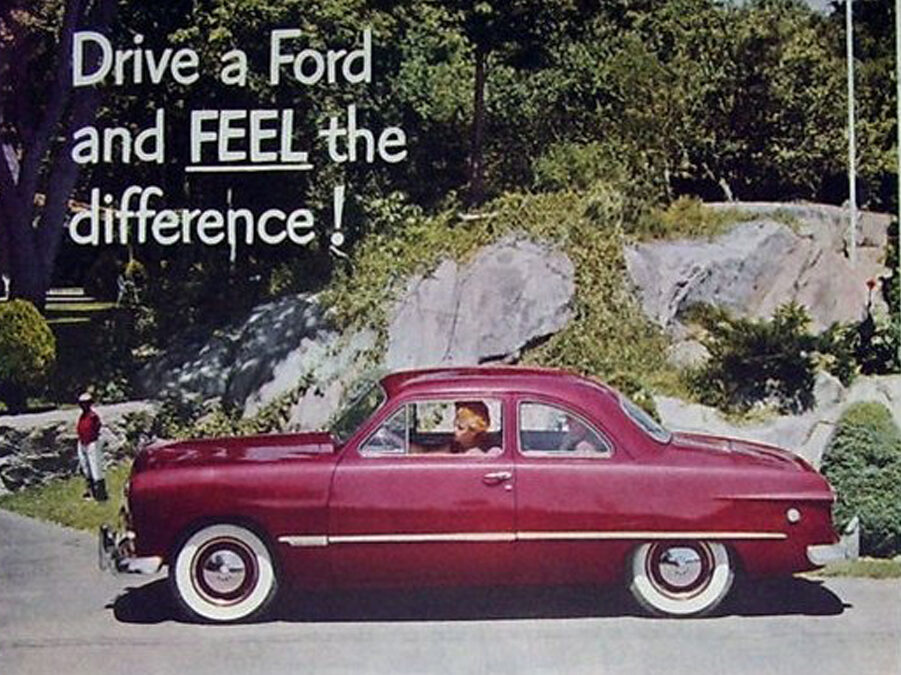

It can be argued that the all-new 1949 Ford saved the Ford Motor Company. It was so different from the 1948 model, and so in keeping with that era’s design trend, that the public embraced it fully.

Ford sold a total of 1,118,762 cars in the 1949 model year. That wasn’t enough to surpass Chrysler, but that would happen very soon. In fact, the 1951 Ford model alone actually outsold Chevrolet.

With the exception of its V8, the 1949 Ford was completely new. It featured new smart-looking, slab-sided styling, a distinctive bullet grille and clean sheet metal. Inside, Ford offered a new front suspension, new shock absorbers, and a simple yet attractive interior.

Also new was a much-promoted ventilation system.

Although the new car had the same 114-inch wheelbase as its predecessor, its overall height was four inches lower. It was also a wider car than the 1948 Ford. An early promotional film bragged that the front seats were eight inches wider and the back seats seven inches wider.

The floor of the new Ford was almost flat, thanks to a lower drive shaft tunnel.

Also noted was the fact the seating positions had been moved five inches ahead. Previously, the rear seat had almost sat on the axle. Ford said its new realigned seats provided greater comfort for the occupants.

The new Ford came with two engines, a six-cylinder that developed 95 horsepower, and the venerable flathead V8 that turned out 100 horsepower.

The car came in two series: an unnamed base model and the more expensive Custom. Available was a two-door, four-door sedan, station wagon and convertible.

The convertible was particularly popular – Ford built 51,133 units. They were available only as Customs with V8 engines, and sold for $1,948.

The cheapest Ford, a six-cylinder base model, retailed for $1,498.

The new Ford was introduced at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City on June 10, 1948, and was released to dealers a week later. Crowds reportedly mobbed the Waldorf ballroom, many of them placing an order without even taking the new Ford out for a test drive.

It wasn’t long before the new 1949 was deemed a hit. Ford eventually sold over 800,000 units. That, plus the Mercurys and Lincolns that were sold (these divisions also benefited from a similar design) pushed the company’s sales to well over one million units, the first time Ford had surpassed that mark since 1930.

The impact on the bottom line for the Ford Motor Company was astounding. In 1946, Ford had posted a profit of just $2,000. Profits under Young Henry’s astute new management team surged to $64.8 million for 1947, but more than tripled in 1949.

And from Young Henry’s perspective, there was more reason to celebrate: Ford sold only 5,000 fewer units in 1949 than Chrysler. But within a year, it regained its No. 2 status.